Inside Job

The difficult situation around insider trading in prediction markets deserves nuance

On January 3rd, hours before dawn, U.S. Special Operations forces extracted Nicolás Maduro from his compound in Caracas. The world learned about it when Trump posted on Truth Social at 4:21 a.m. A Polymarket account called “Burdensome-Mix” had already been positioned for exactly this outcome.

The account was created just a week earlier. It wagered $32,000 on Maduro’s ouster when the market priced it at 7%, and by morning that position was worth $436,000. Burdensome-Mix had bet on exactly four events. All four were about Venezuela.

The political reaction came fast. Rep. Ritchie Torres introduced legislation to ban government employees from trading on prediction markets. The framing was obvious: insider trading.

And look, the instinct makes sense. The timing is damning, the profits are grotesque, and the whole thing has the stench of someone who knew what was coming. But the conversation that followed has been frustratingly shallow, importing assumptions and moral frameworks from securities law that don’t quite fit.

Prediction markets aren’t stocks, and the legal framework governing them is different. The economic purpose is different too. And the technological reality of blockchain-linked liquidity pools makes enforcement of insider trading prohibitions, as traditionally understood, somewhere between difficult and impossible.

This isn’t a defense of the Maduro trade. I’m trying to think clearly about what “insider trading” even means in prediction markets, why the concept doesn’t translate cleanly from equities, and why society is going to have to grapple with a new reality: prediction markets will attract informed money, and that might be fine.

Martha Stewart should have worked at Google, instead

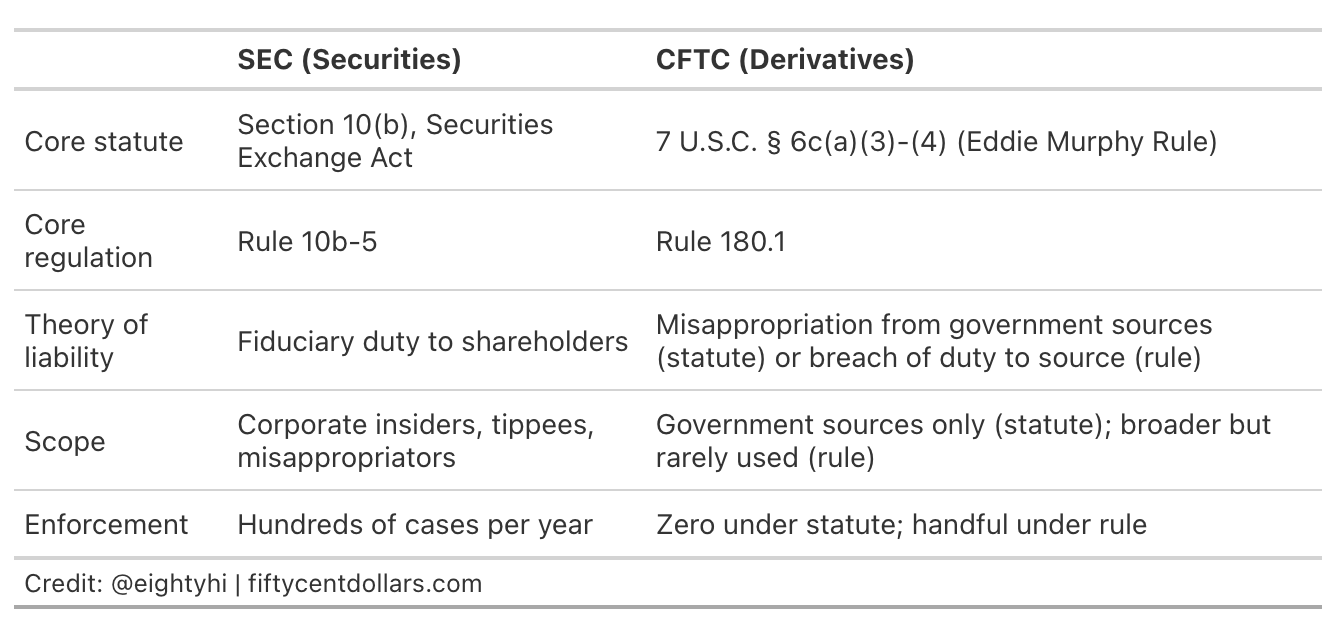

The legal regimes governing insider trading in securities and derivatives are fundamentally different. Most coverage of prediction markets ignores this entirely.

In securities law, insider trading doctrine flows from Section 10(b) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 and SEC Rule 10b-5. The dominant theory is called “fraud on the market”: corporate insiders owe fiduciary duties to shareholders, and trading on material nonpublic information breaches that duty.

Courts have extended this to:

“tippees” who receive information from insiders,

“temporary insiders” like lawyers and accountants, and

anyone who “misappropriates” information in breach of a duty to the source.

The SEC enforces this aggressively, bringing hundreds of cases per year. Martha Stewart went to prison. The doctrine is mature and has real teeth.

The CFTC operates under a narrower framework. Only the misappropriation theory applies to derivatives markets. “Fraud on the market” has no analogue in the Commodity Exchange Act. This distinction matters: derivatives markets exist so that commercial participants can hedge using their own proprietary information. A corn farmer trading futures based on his private knowledge of his own crop isn’t committing fraud. He’s doing exactly what the market was designed for.

The CFTC’s authority splits between a narrow statute and a broad regulation, neither of which has seen much use.

The first tool is the “Eddie Murphy Rule,” codified at 7 U.S.C. § 6c(a)(3)-(4). Added by Dodd-Frank in 2010 and named after the Trading Places scheme that would have been legal at the time, this provision specifically targets government information. It prohibits trading on nonpublic government information that could affect commodity prices, but only if that information comes from federal employees, Members of Congress, or judicial officers.

The scope is narrow by design: nothing about corporate information, private employers, or the vast universe of nonpublic information outside the federal government. Despite being on the books for fifteen years, the CFTC has never brought a single case under it.

The second tool is CFTC Rule 180.1, a broader anti-fraud provision modeled on SEC Rule 10b-5. The only court to fully articulate the standard, in CFTC v. EOX Holdings, set forth a four-part test: the defendant must have:

misappropriated confidential information in breach of a pre-existing duty of trust and confidence to the source;

intentionally or recklessly;

in connection with a commodity transaction;

for personal benefit.

Notice what’s absent from that test: “material nonpublic information,” the SEC’s term of art. Commissioner Caroline Pham has dissented from enforcement actions that conflate the two standards, arguing the Commission should stop “importing non-CFTC terms of art that are inapposite.” The relevant question under CFTC rules is whether information was stolen, not whether trading on it was unfair to counterparties1.

This distinction has practical consequences. Consider a senior data analyst at Google. She has access to internal dashboards showing both the company’s ad revenue trajectory and the “Year in Search” rankings before they’re published. She knows two things the public doesn’t: that Q4 earnings will massively beat expectations, and that d4vd will be announced as the most searched person of 2025.

If she buys Google call options on the earnings information, that’s textbook securities fraud under SEC rules. The information is material to Google’s enterprise value, trading on it harms outside investors who don’t have access to it, and the SEC will come knocking.

If she bets on d4vd on Polymarket, the legal picture gets murkier. The Eddie Murphy Rule doesn’t apply because this is private corporate information, not government data. Rule 180.1 might apply under the EOX Holdings test: she’s arguably misappropriating Google’s confidential information, in connection with a commodity transaction, for personal benefit. Technically, that’s a violation.

But here’s the uncomfortable truth: this enforcement void extends far beyond prediction markets. A Cargill employee who knows the grain harvest will miss expectations could trade corn futures on that information. Under EOX Holdings, that’s misappropriation too. She’s taking Cargill’s confidential data and converting it to personal profit, and so is her brother-in-law if she tips him off. The CFTC has brought a handful of cases against traders front-running their employers’ orders, but the broader universe of corporate misappropriation in commodity markets? Enforcement is essentially nonexistent.

Prediction markets are getting outsized scrutiny because they’re new and visible. The Maduro trade makes headlines. The grain trader who’s been doing the same thing for thirty years does not.

The Torres bill attempts to patch part of this gap by targeting government employees trading on nonpublic political and military information. That’s a reasonable extension of the Eddie Murphy Rule for the most troubling cases. If a Pentagon official bets on operations he helped plan, most people agree that’s wrong.

But the bill doesn’t touch the corporate scenario. Our Google analyst still falls into the same void that’s existed in commodity markets for decades. Technically against the rules, but never enforced. And maybe that’s fine, because prediction markets are fundamentally different from both securities and traditional derivatives.

The question isn’t whether informed trading violates some abstract duty. The question is whether we should care. Can our legal and moral frameworks articulate why it’s different without capturing the entire universe of informed trading?

Knowing things is the point

Why do we care about insider trading in the first place?

In securities markets, the answer is protecting capital allocation. Stock markets exist to direct resources to productive enterprises, and the whole system depends on a basic bargain: prices should reflect publicly available information so that outside investors can participate on fair terms. When a company generates value, its stock price rises, it can raise capital more cheaply, and investors are rewarded for funding it.

Insider trading breaks this bargain. If executives can trade on material nonpublic information, outside investors get picked off, capital allocation becomes a rigged game, and eventually people stop playing. That’s why we send people to prison for it.

Prediction markets serve a different function entirely. They don’t allocate capital to enterprises, they produce forecasts. The “product” is the price itself: a real-time probability estimate that synthesizes the beliefs of everyone willing to put money behind their view. And the value flows not just to traders, but to the much larger universe of observers who consume the price as information without ever placing a bet. Think of how many people check the odds on an election or a championship game just to know what the market thinks. The forecast is the point.

This changes everything about the harm calculus.

Actually, the price is the product

Every six weeks, the Federal Reserve meets to make a decision about interest rates. And, in lockstep, every six weeks economics observers are served up breathless reporting about what the CME FedWatch has to say about what will happen. Everyday people make life decisions based on this information… do I buy a car now? Used or new? Do I refinance my house…

When an informed trader enters a securities market, she gains at the expense of less-informed participants, and the integrity of capital allocation suffers as a result. When an informed trader enters a prediction market, something different happens: the price moves toward truth. The Google analyst who bets on d4vd makes the “most searched” market more accurate. The Pentagon official who bets on Maduro’s ouster (setting aside the operational security nightmare for a moment) makes the Venezuela market more accurate. The information gets incorporated faster, and everyone watching that price benefits from a sharper signal.

The “victims,” such as they are, are the counterparties who took the other side. But what exactly did they lose? They made a voluntary bet based on their own assessment of the odds, and they were wrong. Someone else was more right. In a prediction market, this is the mechanism by which prices become informative. It’s a feature, not a bug.

You might still object that this is unfair. The insider knew and the counterparty was flying blind. Fair enough as an observation, but information asymmetry of this sort is endemic to every prediction market ever created. The PredictIt trader2 who called an energy lobbyist to confirm a tip, the oil trader with satellite imagery has data you’ll never see, or the trader who commissioned proprietary polling will outforecast you on elections.

Nobody calls this insider trading. We call it edge, and we generally think it’s fine because these traders are making prices more accurate, not less.

If you’re trading prediction markets, you should expect to face better-informed counterparties. Some will have better models, some will have better sources, and some will have access to information that would make your jaw drop. By law, no one owes you protection from this. When you click “buy,” you’re expressing a view that the current price is wrong, and so is the person selling to you. One of you will turn out to be more right than the other. That’s how these markets produce accurate prices in the first place.

The distinction that actually matters, I’d argue, is between forecasting and manipulation. A trader who bets on an outcome he can control isn’t bringing information to the market. He’s corrupting the outcome itself. The athlete who bets against himself and throws the game, the executive who buys credit default swaps and then tanks the company, the official who greenlights a military operation and then wagers on its success.

These cases are different in kind, not just degree. The problem isn’t that these people knew something. The problem is that they determined something, and then profited from a certainty they themselves created.

That’s a coherent line to draw. “Did you have an informational advantage?” is not, because in a market designed to surface information, having information is the whole point.

All liquidity is not KYC’d if any of it isn’t

Even if you wanted to prohibit insider trading in prediction markets, you probably couldn’t enforce it.

The reason is technical. Prediction markets now exist across multiple platforms with varying levels of regulation. Polymarket’s international exchange operates with pseudonymous accounts funded by crypto wallets, meaning users can trade without revealing who they are. Kalshi operates as a fully regulated CFTC exchange with know-your-customer requirements, meaning every user is identified, but also blurring the lines with tokenization.

Here’s the problem: these platforms don’t exist in isolation. Arbitrageurs constantly watch for price discrepancies between them. If the same contract trades at 40 cents on Kalshi and 45 cents on Polymarket, an arbitrageur will buy on Kalshi and sell on Polymarket to pocket the difference. This activity keeps prices aligned across platforms, which is normally a good thing. But it also means that adverse orderflow moves freely between them.

This means that, as long as exchanges continue to engage in mimetic competition, a non-KYC’d insider can essentially access all liquidity globally, KYC’d or not.

So, broader enforcement faces hard limits. The confluence of information markets making previously worthless information worth millions and blockchain technology enabling anonymity has set up a chessboard that makes much of this activity inevitable. Society will have to come to terms with a new reality: prediction markets will attract informed money, including money informed by what we’d colloquially call “inside” information.

For serious markets, narrow rules targeting government employees and outcome-controllers might be worth having. For trivial markets, the activity is probably harmless. And for everything in between, the honest answer is that we’re still figuring it out.

The price is the product. Sometimes the people making that price more accurate will be people who knew the answer before you did. Yes, that is facially uncomfortable to some and also, increasingly, unavoidable. Caveat emptor.

Important to note that while the law doesn’t prohibit insider trading per se, Kalshi actually goes above and beyond what is even legally required of them by making and enforcing prohibited traders lists.

🙋 Yours truly, in fact.

This is a great read. One thing I wonder about: in the short run this kind of “insider” edge is good for PMs in terms of accurate pricing, but in the long run could it drive away traders if they start to feel the process is rigged. Then in the long run it could become bad for information aggregation.

your point about how hard this is to prevent given cross market arbitrage is a great one. Maybe there isn’t much that can be easily done

It doesn't alter the article but worth noting that news organisations were also aware of the raid in advance, so it is not clear that the trader was from intelligence services (albeit their source presumably was) https://www.pbs.org/newshour/nation/trump-administration-thanks-the-media-for-keeping-quiet-before-the-strike-that-captured-maduro